All life relies on reproduction, and without it, we wouldn’t exist. The angiosperms, or flowering plants, have mastered the art of sex and are one of evolution’s greatest achievements. The structure of a flower fascinates me. The calyx, which is made up of a circle of green sepals, supports the flower when seen closely. The corolla – the ring of petals that surrounds the sexual organs – is included within this. In flowers, the male reproductive organs are referred to as stamens. The extremities of these bear anthers, which contain pollen. The male sperm cells are found in pollen, a fine powder with a strong coating. Carpels refer to the female reproductive organs. Ovary, style, and stigma make form the carpel; the stigma is located near the tip of the style. For the most part, it’s this one that’s universally recognized. Fertilization occurs via an underground tube formed when pollen grains reach the style’s stigma and germinate.

There are more gymnosperms than angiosperms. Unlike the angiosperms, these plants don’t have ovary-encased seeds, but rather pollen-producing cones. Grymnosperms, such as Scots pine and juniper, are found in the coniferous forests. However, flowering plants greatly outnumber conifers when it comes to variety and distribution. The problem with all of these seed-bearing plants is that they must reproduce while remaining firmly planted. Pollination is an essential part of plant reproduction, therefore they’ve figured out a novel way to move pollen from the anther to the stigma.

Bạn đang xem: How Is Grass Pollinated? Perfect Information For You

The anthers are blowing in the wind

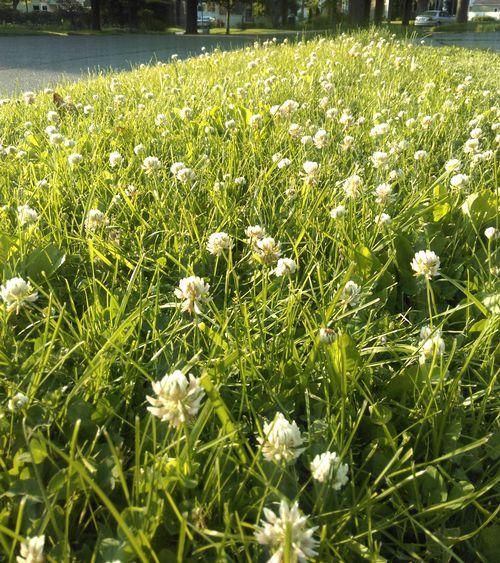

A lot of flowers rely on the wind to transport pollen to other flowers’ carpels. It’s a bit of a crapshoot because the plant has no control over where the pollen lands once it’s in the air. Large numbers are invested in as a way to increase its chances of success. There are tens of millions of pollen grains in just one flower head of an ordinary grass. Each of those only has a little chance to land on one of its own type, thus while the pollen can travel great distances, most of the grains prefer to land within a few meters. In order to improve the chances of pollination, wind-pollinated plants typically grow close together.

The structures of the flowers themselves have also been modified to boost their chances of successful fertilization. Many wind-pollinated flowers have long stamens that are exposed to the wind, and the styles of grasses are sometimes feathered to help them ‘catch’ pollen grains from the air. Astonishingly, some grasses have adapted to discharge pollen during the early morning hours, when the wind is at its most powerful.

Birch (Betula spp.) and hazel (Corylus avellana) contain catkins, which dangle from the branch and allow pollen to be easily thrown off in the wind. Although the leaves of the hazel tree are not yet visible, pollen can travel further from the parent without being impeded by foliage.

Water and pollination

Pollination by water is rare, however some pondweeds are capable of it (Potamogeton spp.). On the surface of the water, pollen travels in two dimensions, rather than three, which is advantageous. This makes it more likely to settle on the water’s surface, where the flowers are located.

Flooding, on the other hand, is a major disadvantage for some insect-pollinated blooms. Heathers like ling (Calluna vulgaris) have developed their bell-shaped blossoms to help shed rain, and it is no accident that they are most common in wet places like Scotland!

Insects and pollen

Pollination by insects is more precise than pollination by wind. It’s still necessary to invest in flowers that rely on insects for fertilization. Advertise, reward, and offer an appropriate landing location for an insect, and most importantly, ensure that pollen is delivered onto the insect.

Flowers are pollinated by a wide range of insects. Flies, beetles, moths, and butterflies are among the most significant, as is the order Hymenoptera, which includes bees. Open flowers like hogweed (Heracleum sphondylium) attract flies and beetles, whereas deeper blossoms like devil’s-bit scabious attract longer-tongued bees and butterflies (Succisa pratensis).

Floral seduction

For centuries, humans have enjoyed the bright colors of flowering plants and insects have been drawn to them as well. However, there is a lot more to the color of a flower than what the naked eye can see. When seen under a UV lamp, flowers that appear to have a uniform color include patterns called ‘honey-guides,’ which bees see at a higher part of the spectrum than we do. Bees are guided to the proper place to collect nectar by honey guides that act as landing lights. Human eyes can see these instructions on some blooms. Flowers such as foxgloves and speedwells (Veronica spp.) feature spots on the petals that lead up to the nectar-filled hole in the center of the flower.

If you’re looking for a pollinator that isn’t already there, you can alter your flower’s aroma accordingly. Heather, pollinated by bees, has a honey-like scent, while honeysuckle (Lonicera periclymenum), pollinated by moths, has a rich, heavy scent, and flies, which pollinate many other flowers, are responsible for the cloying, even unpleasant, smell of flowers like hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna), which smells like carrion, and ivy (Hedera helix) (Vespula vulgaris).

Nectar, a simple sugar solution, is produced by the plant to entice insects to visit flowers. There needs to be a perfect balance between quantity and quality. It’s possible that a potential pollen carrier will become satisfied with the amount of nectar provided by a flower and fly away without stopping at another one (although heather has a trick up its sleeve: if it is not pollinated by bees, its stamens extend so it can resort to using the wind).

Xem thêm : How To Collect Calibrachoa Seeds? Complete Guide for Beginners

Wood anemones, for example, offer pollen as the primary reward (Anemone nemorosa). Bumblebees have pollen baskets on their legs because they eat nectar and pollen. Using these hair-fringed containers, they can carry pollen back to their nests to nourish their larvae, demonstrating just how closely flowers and insects have evolved through time.

Transferring pollen

For this reason, grains of insect-borne pollen typically have a rough or spiky surface, which helps them attach to the pollinator and be picked up by the flower. It is critical that the nectar and anthers are positioned in such a way that the insect may take up pollen in the proper location.

Some flowers have a wide variety of insects drawn to them because they are so open. While some of these products are simple in design, they’ll only appeal to a certain group of customers. Floral architecture and systems are awe-inspiring in their ability to deliver their valuable cargo to insects.

Orchids are one of the most complex flowering plants there is. In fact, the bees drop pollen packets that are attached to their backs and properly aligned for them to be placed on the stigma of the next orchid they come across.

When cultivating a close relationship with specific pollinators, there are both advantages and disadvantages. Pollen is less likely to be wasted by traveling to unrelated species when using this method since it increases the probability of reaching the correct flower. As a species, the plant will suffer if the pollinator declines for any reason, and vice versa. In this case, the interdependence between species is shown to be tenuous at best. Many portions of the Highlands have been overgrazed, resulting in a loss in tree regeneration, as well as a decrease in ground flora, which in turn reduces the diversity of insects.

Bird pollination

Flowers in the tropics are pollinated by birds and mammals, but not in the United Kingdom. There are instances when blue tits can be spotted eating on the male blooms of goat and grey willow (Salix caprea, S. cinerea) despite this. It is considered that nectar-loving bees may play a role in pollination since they like nectar.

Spreading genes

Many people are familiar with the fact that inbreeding is generally bad for a species’ overall well-being since specific flaws or oddities can be exacerbated. So, how can flowers keep from pollinating themselves? There is a brief answer to this question: they don’t always succeed, but they do their best to avoid it!

Rosebay willowherb (Epilobium angustifolium) and foxglove (Digitalis purpurea) have blooms that open in sequence rather than all at once, reducing the possibility of insects visiting other flowers on the same plant.. There are some species that have separate male and female flowers (i.e. flowers with only stamen or stigmas) on the same plant, while there are others that have distinct male and female flowers (i.e. flowers with only stamen or stigmas).

Still others separate plants based on whether they are female or male. This type of plant is referred to as a ‘dioecious’, which is derived from the Greek words “di” and “oikos,” meaning “house” and “ecology.” If you don’t pollinate your plants, you run the risk of not having any pollination at all. Aspen (Populus tremula) is an excellent example of a dioecious tree because it produces both male and female trees. In addition to the lack of blossoms, forest fragmentation means that male and female plants are typically too far apart to produce seed. Dioecious species, on the other hand, have a tendency to thrive in the vegetative propagation arena. When a plant is well-adapted to its environment, such as the aspen stands found in the Scottish Highlands, this strategy can be extremely effective. However, a species like this could be threatened if local conditions change, which is why aspens often flower when they are under pressure or tension.

Some plants, on the other hand, generate blossoms that are tightly closed, allowing them to self-pollinate. Plants that thrive in a given place can benefit from using self-pollination, just like with vegetative propagation. Self-pollination is common in plants that are annuals and may easily spread to new locations. Self-pollination is preferable to no pollination at all since they can easily get isolated and have no possibility of being fertilized or being fertilized.

Pollen dating

The pollen’s outer coating is incredibly durable and can be preserved for thousands of years buried in layers of peat. Pollen grains vary greatly in form and size when viewed under a microscope. Their distinctiveness makes it possible for scientists to pinpoint exactly what kind of plant was present at a specific time. Using this information, we can get a sense of how forests have evolved through time. This strategy has some drawbacks, despite its utility. It’s possible to ignore some species, like the aspen, because they don’t bloom very often. Insect-pollinated trees like birch are difficult to detect with this technique, which favors wind-pollinated trees like those.

Pollination and evolution

Healthy and changing ecosystems are plainly demonstrated by pollination. Plants can avoid competition for pollinators by forming a variety of specialized partnerships with specific insects. “Resource partitioning” refers to this strategy of avoiding competition by diversification and specialization.

An example of symbiosis can be found in the relationship between pollinators and flowers, where the lives of two creatures are entwined. Flowers and pollinators are mutualists when they benefit from each other’s cooperation. A win-win situation for both the insect and the plant. When pollination is effective, seeds form and are spread, but that’s an other topic.

Spikelets

Xem thêm : How To Prune Persimmons? A Few Tips to Remember

Grass reproductive components are organized into “spikelets,” or individual spikelets. Each one is the same as a single blossom in terms of beauty. Grass “plumes” and “wheat sheaths” are two common terms for the clusters of individual spikelets seen in grasses. Plants’ spikelets allow pollen to travel easily from one to the next.

Extra Pollen

It is more efficient to produce vast amounts of pollen than than enormous petals or scents. That makes it more likely that pollen will find its way to the stigma of another flower. When pollinated by the wind, wind-pollinated plants like oaks and grasses tend to overcrowd the land they grow in.

Pollination Periods

According to researchers at the University of Tulsa, grasses begin pollination early May on average. In April, certain native grasses generate pollen, although ornamental and lawn grasses can produce pollen all year long.

When do grasses pollinate?

Most grass pollination occurs in May, but specific types of grass pollinate earlier or later than this. While some grasses generate pollen from summer through fall, others pollinate in the spring. Pollination can begin sooner in the year if the spring is warm, while it will take place later if the spring is mild.

It will be easier to understand a normal grass pollination pattern if you don’t focus on a certain season. For instance, pollination can take anywhere from four to ten days to spread throughout a cluster of flowers. Proximal flowers release pollen first, and subsequently the distant ones follow suit.

This means that pollination can take up to 21 days to occur in a grass field. Dry weather might shorten the pollination time, whereas mild weather can extend it. Grass pollen peaks in the morning and dips in the afternoon due to high temperatures affecting pollen viability.

What affects grass pollination?

When it comes to grass pollination, the temperature has a direct impact on the length of the pollination period and how early or late pollination begins. A change in days or weeks since last year’s pollination, or the time at which pollen is most viable, can indicate this. Pollination is likely to be affected by a variety of environmental factors, including humidity, drought, and nitrogen deficiency.

The use of glazed paper bags in the pollination of grasses has been studied and found to have favorable impacts on grass pollination. Greenhouses can help keep plants safe from environmental factors such as low humidity (which reduces seed production) and rains (which reduces pollination).

How do grasses reproduce?

To clear up any misunderstandings, grasses can still reproduce sexually by seed and by cross-pollination by gardeners. Stolons, rhizomes, nodes and buds can also be used to reproduce grasses in vegetative propagation. Considerations must be made whether you want to focus on self-pollination and cross-pollination.

Some grasses, like cereal grains, have cleistogamous grass florets that can easily be pollinated by themselves. Although monoecious and dioecious grasses can cross-pollinate, dichogamous species cannot. Finally, chasmogamy is required if you want to grow species that can both self-pollinate and cross-pollinate at the same time.

Conclusion

Gardening is a lot easier when you understand how plants reproduce. When it comes to grasses, you may question how they’re pollinated when there are no insects around. Flowers in grasses, in contrast to those in other plants, are not brightly colored or fragrant in order to attract insect pollinators.

You can conclude that grasses rely on wind pollination based on these data. They produce a lot of pollen, and that pollen should be able to travel a long way to provide a steady supply. A few scientists and gardeners still employ seeds or cross-pollination for grasses, though.

As far as advantages go, wind pollination is simple and predictable, with little potential for error from the gardener’s perspective. You can also use a greenhouse to keep pollinators away from your lawn. Temperature, humidity, and rainfall all affect the length of the pollination period and when pollination begins.

Nguồn: https://iatsabbioneta.org

Danh mục: Garden